|

When you visit a dentist, you expect to receive treatment which reflects best practice. When you employ an architect, you expect their designs to meet all the current regulations. Chiropractors must adhere to government mandates. And when you visit a doctor, you expect them to follow stringent guidelines to cure your ailment. Why should teaching be different to these other professions? The ideal of 'teacher autonomy' is a pervasive one. It is evident in statements about individual teachers being the ones best able to meet their students' needs. It exists in the dismissal of experts in other fields "who wouldn't understand because they're not teachers". It is seen through the belief that the pedagogical knowledge of an individual trumps the collective wisdom of research. Idolisation of teacher autonomy is not only pervasive; it can be deeply unhelpful to our profession. The idea that an individual teacher is the one best placed to meet their students' needs is a seductive one. It can be seen in recruitment campaigns to "be that teacher". But what happens if you are not meeting the needs of a child? The premise of teacher autonomy has now placed that individual teacher to blame. I think about the number of newly qualified teachers who leave the profession and wonder how many leave because they have been overwhelmed with too much choice. Teacher autonomy also leads to the idea that we can not use resources that have been prepared by somebody else. This wastes countless hours of teachers and burdens them with an unnecessary workload. The reality is that teachers need to draw on our collective experience and wisdom. We need to support each other. Of course, children are unique, but this is an argument to uphold one another, not to be left to flounder in freedom. Teacher autonomy is an unhelpful seduction because it inadvertently isolates us from our colleagues. When we go to our GP, we are not surprised when we get a referral to a physio, or a psychologist, or told to get a blood test, so the pathologist can have a look. Health professionals work with each other to provide what an individual needs. Why then do we ignore (or even belittle) the advice of experts from other fields? Of course, we specialise in education but, given the complexity of children, we need to be willing to accept assistance and wisdom from other fields. This cannot be only when we ask for it, because that is not a healthy relationship. Teacher autonomy is an unhelpful seduction because it isolates us from other professions. Teacher autonomy enables teachers to self-select their own standards of evidence. This sounds enticing, but it allows for the anything to be considered acceptable research. A perfect example of this is the seemingly endless debates that exist around reading. The US's National Reading Panel (2000), Australia's Rowe Report (2005), and the UK's Rose Report (2006) all had similar findings that systematic phonics is essential for reading. Yet, the debate rages on because teachers are empowered to put ideology over evidence under the guise of 'autonomy'. If a doctor, dentist, or architect used their personal beliefs to ignore the evidence-backed guidelines, it would be called 'malpractice'. Teacher autonomy is an unhelpful seduction because it isolates us from implementing best practice. Teaching is the most noble profession. We are entrusted with the care and nurturing of children. It is our mission to enrich the lives of our students and teach the new concepts, help them master new skills, and learn how to be active participants in our world. Of course, teachers still need choice, but it cannot be unrestricted. Teachers still need voice, but we must also respect the wisdom of others. Teachers still get to rejoice as we enable strong research evidence to become embedded practice. Let's stop making the ideal of teacher autonomy into a false ideal so that we can collectively create a strong education for every child.  Photo by Sven Mieke on Unsplash

0 Comments

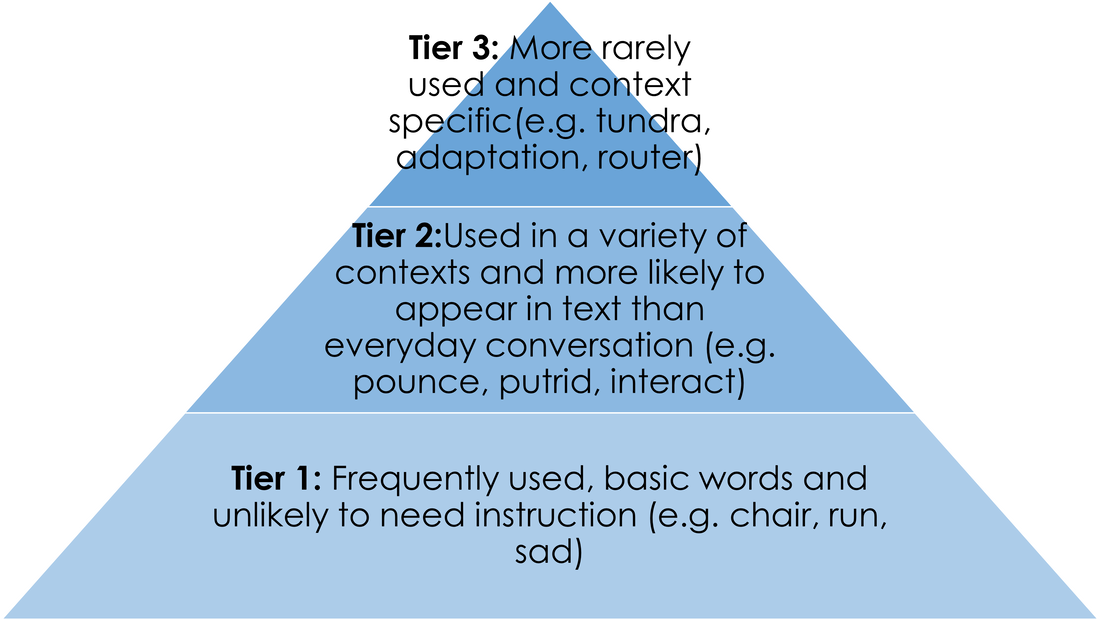

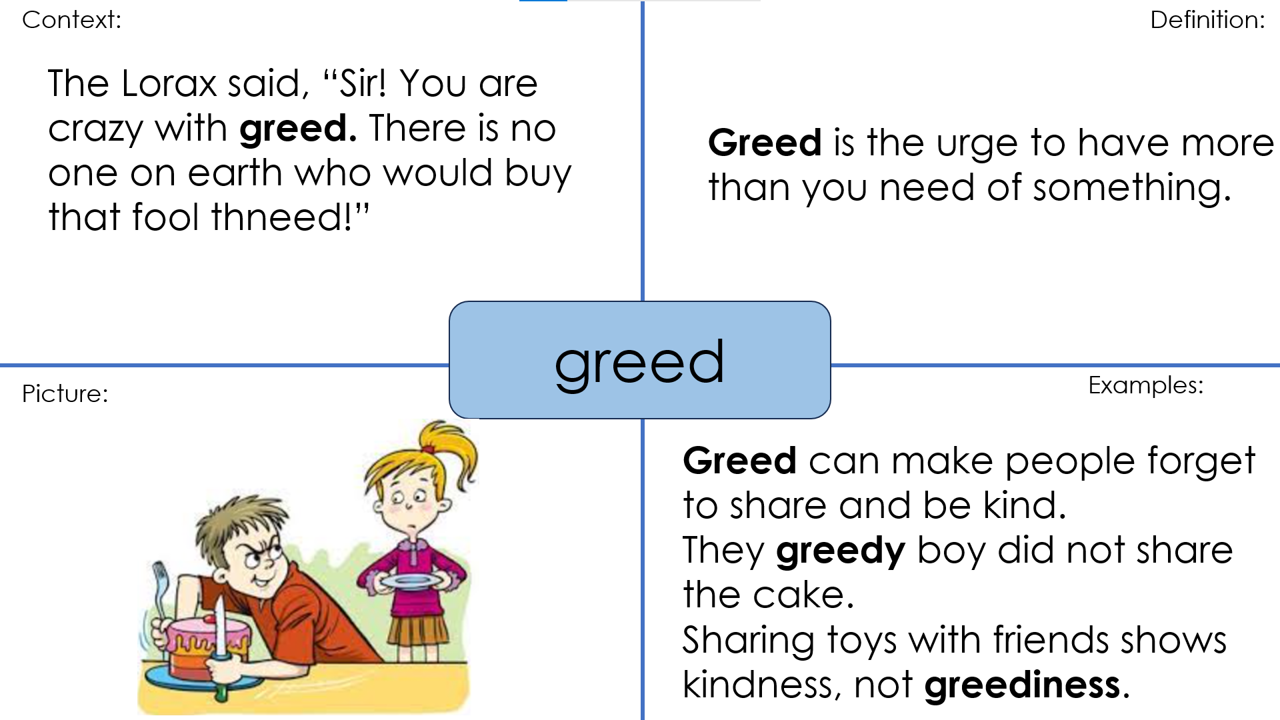

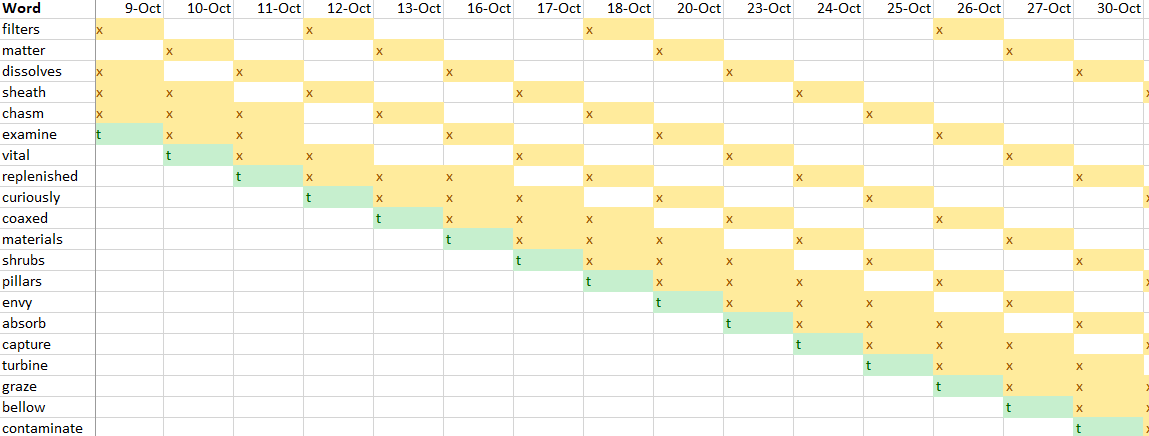

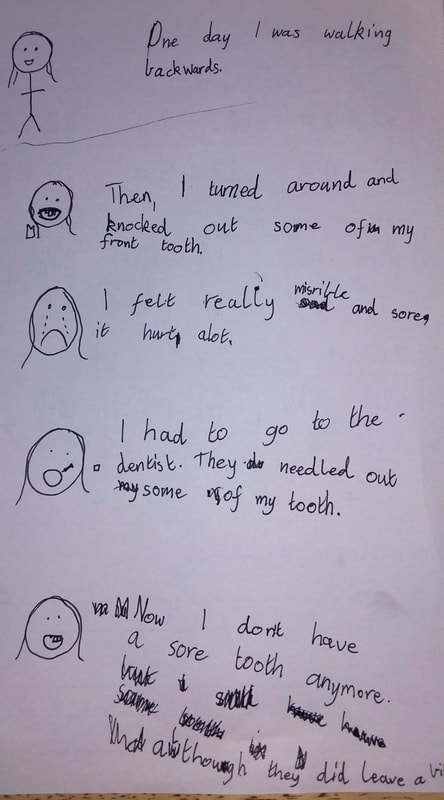

To the attention of the Australian Education Union Victorian Branch, I am deeply appalled, devastated and hurt by the statement passed unanimously by the joint Primary and Secondary Sector Council on the 14th of June, 2024. As a passionate advocate for public education and a long-time member of the union I am puzzled by the stance put forward because it fails to support equality in education, downplays the importance of phonics in learning to read, and dismisses the hard work many members are already doing in their schools while increasing our workload. I am deeply appalled that the AEU Vic fails to recognize the huge leap that the Minister’s announcement at the Age Education Summit is for equality in Victoria. Literacy is a social justice issue. Every child, regardless of background, has the right to be literate. While I applaud the AEU’s advocacy around school funding, I am appalled that the union is objecting to a move to make literacy education equitable. Victoria may be leading the other states in our NAPLAN results for reading, but still 1 in 4 students in Grade 3 fail to be proficient readers. This situation is worse for our disadvantaged, regional, rural and First Nations students. This is not an acceptable situation and the union should be actively supporting moves to change this. Ensuring that phonics is taught in all schools is the biggest lever that education can pull to achieve equity in our state. I am devastated that the union has downplayed the importance of phonics in early reading. The willfully misleading phrase “that a range of teaching strategies to teach reading, including phonics” does not demonstrate a sound knowledge of critical importance of teaching phonics to all students. The National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy was conducted almost 20 years ago and clearly articulated the need for systematic phonics instruction, as the Minister is finally advocating. English is a morphophonemic language and all students need to be taught how to unlock the code that is written English. Early systematic, synthetic phonics is essential for all students. The Minister should be applauded for finally embracing this crucial aspect, not subjected to unfounded criticism for “a lack of understanding”. I personally witnessed the Minister engage with Professional Learning on early literacy, handwriting his own notes, staying for several hours after his address, and consulting with a wide range of teachers, principals and other educators during the breaks. The union should be applauding that we finally have a Minister FOR Education in the Education State. I am deeply hurt by the stance that the union has taken because it dismisses and disrespects the hard work that I, alongside many other teachers, have put into creating change for our students and in supporting teachers. I have introduced the explicit teaching of systematic phonics in multiple schools. Often this work has not been supported by the broader department and yet I, and many other members, have persevered- attending PL outside of contracted hours. A key piece of feedback from the teachers I support has been how much this approach has reduced their workload. Providing high-quality instructional resources results in teachers having a decreased burden in their workload. The union keeps highlighting this is the number one issue for their members. Why is the union objecting to a key reform that will alleviate the burden of workload from its members? Instead, the union has taken a stance that drives a wedge between teachers. I now do not feel supported, or even respected, by the union that is meant to stand with me in solidarity. It should also be noted that this reform will not only ease the burden of our early years teachers. Differentiating for the broad range of students’ abilities adds hugely to teachers’ workloads. Often this stems from poor instruction (typified by whole language or balanced literacy) in the early years that leads to our significant number of students not being able to read at a proficient level. This reform seeks to finally address this issue in a meaningful way. How does the union propose to reconcile the sense of appall, devastation and profound hurt that I, a loyal member and proud public teacher, feel in this statement against these reforms? These reforms have the potential to make a profound difference in not only our students lives, but also the wellbeing and professionalism of our teachers. I am carefully considering my future as a member of the Australian Education Union- Victoria Branch Yours in hopeful future solidarity, Edit: The AEU Vic Branch's statement can be found here I've just realised that I've created over 700 slides in the first four weeks of term. Why? Because our school has introduced a consistent way to teach and review vocabulary. Why is teaching vocabulary important? Vocabulary is one of the five keys of reading (along with phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency and comprehension). Teaching vocabulary is important in laying a foundation for students to build on. Students who know what a wider variety of words mean are able to unlock the meaning of texts more successfully than the child who struggles to understand what different words mean. In fact, students who have a broader vocabulary will also be better equipped to determine the meaning of unknown words when they encounter them. This is an example of the Matthew effect, where "the rich get richer and the poor get poorer." This is an equity issue because students with limited vocabularies will struggle to learn new words from context alone and comprehend the full meaning of texts. What words should we teach? Given the vast number of words in the English language it is nigh on impossible to teach every word at school. I did the maths: it would require teaching a unique word every five minutes! If we can't teach every word, which ones should we spend time focusing on? Students come to school already knowing many common words (tree, happy, shop, ball, tired). We don't really need to teach these as many children already know how to use these words. Of course we may need actively teach these if students come to us from language backgrounds other than English, or have developmental language delays etc. There are also words that have a specific definition that is context dependent. We don't use these words unless we are referring to that exact thing (pedagogy, atmosphere, hypotenuse). These words need to be taught when we are teaching about that particular topic. The rest of the words are used in a variety of different contexts and are what makes English such a rich language. This area include words like delectable, envy, graze and greed. These words are more likely to appear in written English, rather than spoken- which is one reason we need to ensure students have time to explore rich texts in class. I also think that this category of words are the ones that we can get the most bang for our buck- when students learn these words they can use them in a range of contexts. These three categories of words can be referred to as tier 1, 2 and 3. While there are definitely times when we need to explicitly teach tier 1 and tier 3 words, most of our time should be focused on tier 2 words. These are the types of words that students can use repeatedly in different contexts. It should be noted that these tiers are not distinct and there is plenty of grey area between each tier. A guiding principle in selecting words at our school has been: which words do I want to see my students use? How should we teach vocabulary? Once upon a time when I was teaching a new word to students I would first ask them if anyone knew what it meant. This typically resulted in students telling me definitions that were incorrect, or at best partially correct. The problem I then faced was, not only had I wasted a few precious minutes of instruction, but other students had now heard incorrect definitions and may have developed fresh misconceptions. At my current school we follow a simple procedure to explicitly teach new words:

Our review activities include matching words to definitions, working out what word fits in a sentence, and coming up with our own sentences. I started to get even fancier with the variety of activities in our review, but quickly realised that keeping it simple was better for our students. Instead of having to think about what each activity is asking them to do, they are free to focus on retrieving the words they have previously learnt. Likewise, I also started to explore word matrices, but again realised that this was overcomplicating it (for the moment).

If you want to see a sample week then click here. Resources: I use etymonline.com for the teacher notes. I've found wordsmyth.net gives consistently student-friendly definitions. Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction by Beck, McKeown & Kucan is my go to resource. It is the spring holidays here in Australia. We are experiencing a burst of gloriously sunny days. Yesterday, I dusted off my bike, squeezed into my lycra and went for a ride through the rolling hills of the goldfields were I live. Despite having not ridden since last summer, my skills came back to me: I knew when to change gears, when to get out of the saddle, how to navigate the bends in the road, to listen out for cars that were approaching, and managed to have a conversation with another rider I met along the way. The idiom 'it's like riding a bike' rang true as skills that I haven't used for the best part of a year came flooding back to me. I was even able to navigate the swooping magpie as it hit my helmet four times. Riding a bike is a skill that I have mastered. I didn't have to consciously think about each skill as I did it. If I hadn't mastered these skills then it would have been much harder to deal with the angry magpie as I would have needed to think about how I could watch its shadow out of the corner of my eye, duck at the right moments while pedalling, changing gears and steering. Mastery learning has an essential place in education. However, it wasn't a term I had come across until I was trained in Direct Instruction. The idea that we want students to understand concepts "as well as their own name" became transformative in my teaching. Through mastery learning I expect my students to learn many things without the need for conscious thought. As I learnt about cognitive load theory, the importance of mastery learning became more obvious. Mastery learning allows us to free up our working memory because we have stored things accessibly in our long term memory. If students are able to recall knowledge and concepts without active thought then it allows them to concentrate on applying this knowledge in more complex ways. A student who hasn't learnt their phoneme-grapheme correspondences automatically will struggle to read fluently or comprehend what they have read. A student who hasn't mastered their times tables will struggle to solve a problem that requires students to identify factors. I never truly mastered my musical scales and know how hard I had to think about each one before I played it. Meanwhile my friend who mastered his scales now plays for a world class orchestra. Teaching to mastery also means that students are less likely to forget things. This is enhanced by implementing regular reviews in the class. Reviews can be fast-paced if students have mastered concepts. Reviews allow students the opportunity to recall previously learnt material and the more frequently they are given this opportunity, the stronger the pathway to this knowledge is. While Direct Instruction remains an epitome of mastery learning, Ochre Education is creating new resources for Australian teachers to implement mastery learning through explicit instruction in their classrooms. AERO has put out a guide about Mastery Learning and there are many UK-based resources on this topic as well. It is easy to forget how important it is to learn things to mastery. The claim that we need to move away from facts-based education to broader concepts such as critical thinking is typical of this amnesia. How can you think critically if you don't have fundamental knowledge to base it on? I know that I could only analyse Debussy's Nocturnes because my music teacher took the time to teach us about the impressionism movement that occurred in the visual arts. A similarly condescending cry is that we can 'just google it' (or 'just ChatGPT it'). The ability to access a vast array of information actually emphasises the need for a good grounding in common knowledge, otherwise we are unable to understand which links are useful, accurate or relevant. Our students deserve to be taught to mastery. Our students are capable of understanding concepts and knowledge to a level of automaticity that they know it 'as well as their own name'. Let's ensure that every child gets an education that empowers to build on this knowledge.  Image by Moshe Harosh from Pixabay I've just come back from a quick trip to Sydney, where the light display, Vivid, opened. While I enjoyed seeing the Opera House and Harbour Bridge illuminated, the purpose of my visit was to learn more about a language intervention called 'Story Champs'. I'd heard whispers about this program and how effective it is, but I'd never seen it in action and was hesitant about the price of shipping it from the US. So when the opportunity arose to order it with free shipping and attend face-to-face PL on it, I jumped on the chance! I joined a room full of speech therapists, as one of a handful of teachers (and one grandparent who wanted to learn more about supporting her grandchild). We heard from Dr Trina Spencer and Dr Douglas Peterson who met as doctoral candidates and discovered they were both passionate about literacy development. Their research led to the creation of Story Champs and the CUBED assessment both of which are available from Language Dynamics. The science of language and reading is becoming more mainstream. It is great that the skills needed for the word recognition side of the simple view of reading are becoming more common in Australian classrooms. It is important that we ensure we are also teaching language comprehension skills. The focus of my day yesterday was on how we can effectively and systematically teach these skills. Oral language is the foundation for all our literacy skills. It needs to be taught first and continuously. The stronger our oral language skills, then the stronger our reading & writing will be. After all, if you can't understand something when it's oral, then you won't understand it when it's written. There is a clear emphasis on developing oral language skills in the early years. However, how much of this development is done in a systematic way? And how do we know? "Weighing a pig won't help it grow, but what gets tested gets taught." The importance of assessing oral language so that we actually know what we need to teach our students led to the creation of CUBED. This (free) assessment is broken into 2 subtests that address the 2 factors of the simple view of reading.

I used NLM:Listening for the first time last year. I was impressed that I could assess of a child's comprehension without the need for the student to decode anything. It let me lift the lid on what the child understood without their decoding being a potential barrier. There is a third version of CUBED about to be released. This edition will extend CUBED beyond the current K-Grade 3 offering up to 8th Grade. I am excited about what this will mean for assessing the comprehension of our upper primary students. Weighing a pig is one thing but you need to know what to feed it to fatten it. This is where Story Champs fits in. To develop systematically oral language skills Story Champs combines 3 active ingredients:

Story Champs aims to make the patterns of stories obvious. I saw this firsthand this morning when I went through a story with my 4yo. He quickly picked up how to retell the story and was then able to generate a personal story following the same pattern. The 7yo saw what was happening and so I chose a slightly more complex story and she just as quickly picked up on the pattern. She also added to her vocabulary along the way (tentatively, resolved, radiant). The 7yo even wrote down her personal story. This week I am planning to use the CUBED NLM:Listening assessment with my class. I am looking forward to start using Story Champs. It will probably be once a week, with our read-alouds the other four days focusing on building background knowledge. I can also see the huge potential benefits for students in our intervention program in both small groups and 1:1.

Recently I was listening to an audiobook. Thanks to a dodgy Bluetooth connection, every couple of minutes a word was skipped. Most of the time, I could work out what the word might have been. It was tedious, but I could still follow the story. Until it cut out as they mentioned “the myth of…”. I had no context for what that missing word might be. There were very few clues in what I had heard. I had even caught the initial sound of the word, but given that there are over 4000 words starting with ‘m’ (according to a scrabble dictionary), this was of little use. I was left frustrated and perplexed. It wasn’t until they later repeated the phrase that I knew they were discussing “the myth of measurement”. As a fluent reader, I could fill in most of the blanks despite my dodgy Bluetooth connection. However, this is the complicated guessing game that occurs in many classrooms under the guise of reading instruction. Three cueing is the misguided belief that we need to consider the meaning, syntax, and visual information to decode words. Instead it promotes guessing based on context or using clues provided by pictures. This style of instruction is evident in the current Victorian Curriculum Foundation English elaboration, which has students “attempting to work out unknown words by combining contextual, semantic, grammatical and phonic knowledge”. Of course, context is important in comprehending the text. However, the first step towards understanding must be accurate decoding. To create readers who are good decoders students need to be able to orthographically map words, through linking letters with the sounds they represent. To achieve this, we need to explicitly and systematically teach phonics. Decoding occurs when we focus on the letters in front of us and process them in order. If I am looking at anything other than the text on a page to decode, then I am just guessing. Of course, phonics is only one aspect of reading, but it is an essential skill. Students who can decode words have a much better chance at comprehending the text in front of them. I recall a student who was reading chapter books. Whenever he got to a word he didn’t recognise, his eyes would jump to the small picture. This child was unfortunately an instructional casualty of three cueing. He had inadvertently been taught that he would understand the word if he looked somewhere other than the word. This is exactly the type of reading behaviour that leads to a ‘third-grade reading slump’. Three cueing is often seen as a hallmark of ‘balanced literacy’. Although there is no clear definition of what balanced literacy actually is, it is nevertheless a popular term in Australian schools. It certainly featured prominently in my training as a primary teacher just over a decade ago. One of the texts we were referred to was Fountas & Pinnell’s chapter called ‘Guided Reading Within a Balanced Literacy Program’ (1996). So imagine my surprise when the same authors posted a blog last year distancing themselves from the term ‘balanced literacy’! Unfortunately, this shift away from the ‘balanced literacy’ label doesn’t seem to coincide with any substantive change in their approach to teaching reading. Last year, social media erupted as a moderator for Fountas & Pinnell’s facebook group suggested that we should accept that 20% of students will be unable to read proficiently. I am not sure where this figure came from, and Fountas & Pinnell have since apologised. However, to claim that 1 in 5 was an acceptable rate of failure caused an understandable outburst. Imagine the outcry if 20% of students didn’t have lunch! This equates to over 800,000 current students in Australia. As educators, we should not accept this high number of instructional casualties. Emily Hanford's latest podcast Sold a Story is shining a light on practices that are common in many classrooms. Well-meaning teachers are unintentionally teaching their students how to be poor readers. Instead of teaching students to effectively decode words, we are telling them to look at pictures or use cues other than the words themselves. This is leading to students becoming instructional casualties. Good readers decode words accurately and automatically. This is what we need to be teaching our students to do in order to avoid any more instructional casualties. There are far too many stories of children who are instructional casualties of three cueing. The devastation, heartbreak and illiteracy that are perpetuated by the prevalence of this practice is shocking! Think about your family and friends. How many of them are you willing to allow to be instructional casualties? How can we possibly condemn such a large proportion of them to a life of struggling to read? Three cueing, by its nature, leads students to guess at words. This creates instructional casualties who become poor readers. Our children deserve to be taught the skills they need to decode words accurately. Teaching phonics systematically and explicitly as part of our literacy instruction empowers every child to read. A version of this article originally appeared at https://educationhq.com/news/heartbreak-and-illiteracy-three-curing-creates-instructional-casualties-108331/  Image by Patrice Audet from Pixabay There has been quite a buzz created by Emily Hanford’s latest podcast Sold a Story. If you haven’t listened to it yet then I strongly encourage you to do so. At the time of writing I am eagerly awaiting the third episode to be released. Over the last five decades cognitive scientists, psychologists, and researchers have unveiled a lot about how we learn to read. Emily Hanford is exploring why this knowledge hasn’t made its way into our classrooms. There is a different idea about how students learn to read that is much more popular and prominent is schools and education faculties. “Here’s the idea. This origin of this idea is the focus of the second episode of Sold a Story, particularly focusing on Dame Marie Clay’s work and the Reading Recovery program she founded. It should be acknowledged that Clay did some important work in advocating for early intervention and remediation for students with difficulties learning to read. However there are aspects of her work that do not hold up to scrutiny today. I was taught this idea that beginning readers need to use cues, such as a picture, or grammatical structure, to decode unfamiliar word at university just over a decade ago. My first school used Reading Recovery as its intervention program. I remember being gently rebuffed when I tried to work out what students in my class were doing in intervention so that I could better support them in the class. Little did I know how expensive this program was, both financially, and also in terms of costing children the chance for effective reading instruction. Reading Recovery is an expensive intervention. It costs to train a teacher in Reading Recovery. According to their Australian website you must have at least 5 years’ experience teaching before embarking on a yearlong training course. These teachers work with students 1:1 for half an hour, five times a week for 10-20 weeks. In Victoria, this equates to a cost of over $2500 for every student who receives a 10-week Reading Recovery intervention. While expensive, it could be argued to be worth it if Reading Recovery was an effective intervention. However, numerous studies have indicated that any short-term positive impacts from this intervention are not sustained. The real cost of Reading Recovery is that precious instructional time is spent teaching children to focus on words in inefficient ways. Clay was aware of different theories of how we read, claiming “On the one hand the traditional, older view sees reading as an exact process with an emphasis on letters and words, while on the other hand, a more recent set of theories sees reading as an inexact process, a search for meaning during which we only sample enough visual information to be satisfied that we have received the message of the text (Clay 1979, p.1- emphasis is mine). This idea using just enough visual information alongside other cues is a recurring theme in Clay’s writings. She explores the idea that “text carries redundant information, more than the reader usually attends to (Clay 1991, p.331). This idea is explored through by blanking out a number of letters or words in passages to demonstrate how good readers supposedly ‘problem-solve’ or predict as we are reading. I am not quite sure how these activities aren’t guessing. In fact Ken Goodman, who according to Clay was a leading authority on the reading process, refers to it as the ‘psycholinguistic guessing game’. It’s interesting to note that Clay suggests that we should observe eye movements, as this is exactly what scientists started to research in the 70s. It became really clear that, instead of just sampling the letters in a word, proficient readers track every letter in each word in order. The idea that readers just need to get an approximate shape of a word was clearly debunked in the 80s (Ehri & Wilce 1985). It was demonstrated that proficient readers use their knowledge of phoneme-grapheme correspondences to decode words accurately and seemingly automatically. Clay appears to be aware of this research, having referenced Ehri in 2005. Unfortunately, systematic phonics is not something that Clay advocated for. A trusted colleague has told me that when they were trained in Reading Recovery they were told to never use the prompt “sound it out” to a child came to a word they had difficulty with. By 2005 there was an acknowledgement that some phonics instruction was needed within Reading Recovery, it appears to be analytical, where the focus is on breaking a word gradually into smaller parts. There does not appear to be a clear scope and sequence to this approach. In fact they appear to be discouraged as Clay states “teaching sequences of a standard kind are unlikely to meet the needs of struggling students”. The resulting ‘word-work’ (avoiding the term phonics) activities are somewhat baffling. Clay suggests that no more than 2-3 minutes per half-hour session is spent ‘taking words apart’. This limits the crucial phonic knowledge that struggling readers need in order to be able to gain meaning from a written text. There is also a big focus on separating words into onset & rime, which is a less efficient strategy than teaching how to blend individual phoneme-grapheme correspondence. There is a more subtle yet equally worrying argument that emerges throughout Clay’s work. The idea that “well-prepared children seldom fail to learn to read” (Butler & Clay, 1987, p37) implies that if a child doesn’t learn then blame can be placed with their home background. I believe that this is a dangerous idea. It creates division between educators and families. Of course, students come from a wide variety of experiences before school. However, educators should take ownership of the things within our control. Ensuring that every child receives quality literacy instruction is the core work of teachers. I don’t understand why people continue to defend Clay’s work as the basis for effective intervention. It is costly and doesn’t have long term positive effects. Struggling readers are taught to use cues other than the word when reading. The limited, unsystematic approach to phonics further compounds the disadvantage that struggling readers. Readers who struggle must be taught how to decode in order to gain any message from a written text. “There is a message here. We adults may be wrong about what we think the child needs to know, to read.” I wonder how many more people would be able to read today if Clay had heeded her own words.

References: Butler, D. & Clay, M. (1987). Reading begins at home. Heinemann Publishers Clay, M. (1979). Reading: The Patterning of Complex Behaviour. Heinemann Education Books Clay, M. (1991). Becoming literate: the construction of inner control. Heinemann Education Clay, M. (2005). Literacy lessons: designed for individuals, Part 1 & 2. Heinemann Education Ehri, L. C., & Wilce, L. S. (1985). Movement into Reading: Is the First Stage of Printed Word Learning Visual or Phonetic? Reading Research Quarterly, 20(2), 163–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/747753 It's a bit of a weird thing for a teacher to spend their Sunday at a professional learning. But I'm not the only weird one and I joined hundreds of other people passionate about education in Melbourne today at LDA's event 'A Day with Linnea and Friends'.

LDA (Learning Difficulties Australia) somehow managed to lure the Professor Linnea Ehri to Australia to receive the 2022 AJLD Eminent Researcher Award. When I heard that she was presenting in Melbourne I booked a ticket before I had even consulted my wife! Alison Clarke (founder of Spelfabet) had the MCing duties and introduced each speaker wonderfully, as well as hosting the panel discussion brilliantly ( and had the dubious privilege of sorting out the initial tech issues). Professor Ehri spoke eloquently about the research she has done about how children learn to read. Her work on orthographic mapping is something that all teachers of English and literacy should understand. Orthographic mapping is reliant on children having the knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondences to be able to decode and encode written words. This is the process that enables us to recognise words almost instantaneously. I'm not going to go in too much detail as Professor Ehri will be presenting with more of her friends in Sydney on Tuesday, but I found the level of detail her studies on the Four Phases of Word Reading and Development went into fascinating. I was particularly intrigued by her findings when she compared instruction of syllable units against grapheme-phoneme units (in Portuguese). I believe that this level of intricacy is exactly what we need to disseminate further to help inform our teaching practice. After a morning tea break full of discussion we were back to listen to Emina McLean. Emina is the Head of English and Literacy at Docklands Primary School, trains pre-service teachers and student speech pathologists, provides professional learning, consults and is a guru on education. She is also the co-recipient of the Mona Tobias Award. Emina spoke about excellence and equity in Australian education and how Docklands PS is trying to achieve both of these. My hastily scribbled notes say: excellence = finding success for our students equity = ensuring ALL students are successful Emina unpacked four ways that Docklands PS does that help build excellence and equity.

The other co-recipient of the Mona Tobias Award was Dr Nathaniel Swain. He is the founder of Think Forward Educators, a teacher, instructional coach and researcher. Nathaniel encouraged us to reflect on our literacy instruction so that we can more effectively teach. He encourage us to teach the basics well, not so that we can go 'back to basics' but so we can move beyond the basics. A whirlwind tour of word instruction at Brandon Park Primary School, saw us looking at graphemes, words, morphemes, sentences, and extended texts through PhOrMeS and Read2Learn. The tinkling bell came all too soon to signal time was up. Jocelyn Seamer was the recipient of the Bruce Wicking Award. Jocelyn is an educational consultant with many (and varied) years of experience as a teacher and school leader. She talked about how we need to help support our colleagues as we embrace educational change. Jocelyn unpacked the value of working with our colleagues and how, like we do with our students, we need to meet them at their point of need. At times this involves coaching, supporting, directing and delegating. We need to be as intentional with mentoring as we are with our teaching. Lunch was another golden opportunity for discussions with others. It was nice to put faces to people I've previously only met online. And all too soon we were heading back into the theatre for the next session. Dr Jennifer Buckingham is the founder of Five from Five and is an expert on educational policy. She led us on an exploration of the policies in literacy education over the last twenty years. The messages from the Boys' education inquiry in 2002, the Rowe report (2005), and Dyslexia Working Party report (2010) all seemed very consistent that schools need to be teaching "a strong element of explicit, intensive, systematic phonics instruction” (Boys' education inquiry, 2002). And while it might feel like no progress is being made, Jennifer shared positive examples in the changes in the Australian Curriculum, the increased uptake of a Year 1 Phonics check, the SA Literacy Guarantee unit, and the Catalyst project of Catholic Education Canberra Goulburn. It was time for the panel discussion, which saw all our presenters gather and answer questions that had been submitted throughout the day. There was talk about whether graphemes should be incorporated into phonemic awareness instruction, the usefulness of spelling tricky words, the importance of primary schools getting literacy instruction right, the need for secondary schools to have a consistent approach to supporting their students. And Emina gave me a new motto for school change "Less, done well, is more." Then it was time for us all to go home (after a bit more chatting and navigating the Greek Festival), and more importantly to our schools and communities to keep improving our literacy instruction so that all children can achieve their success. I got into teaching because I love mathematics. My first foray into teaching was as a year 11 student tutoring a friend in year 8. I managed to help them get their grade from an E to a B and this sparked a fire in me. I wanted to help others learn about this wonderful world of numbers. When I graduated from uni I somehow believed that in order to effectively teach Maths I needed to get my students to discover it for themselves. I felt like a magician, planning experiences that would reveal a deeper understanding of all things mathematical. If only I knew then what I know now... I was busy providing activities that I hoped would allow students to unearth the enigma of mathematics. I should have been actively teaching them the things I hoped they would discover. After all, I was the expert in the room. "If a student hasn't learnt, then the teacher hasn't taught." Like many educators, I strive to improve. The last few years I have been considering how to best teach students Maths. I've finally settled on a framework that is supporting my students to achieve some amazing outcomes. This model is heavily influenced by Rosenshine's Principles of Instruction. It also ensures that due attention is given to each of the proficiencies of understanding, fluency, problem solving and reasoning. You will notice though that the prerequisite skills required for these proficiencies are explicitly taught to students. For want of a better phrase, I call it Revise-Learn-Apply. 1. Revise In my first year of teaching I observed a colleague run a Maths lesson. He started it off with students answering 10 questions from the board. These questions covered a range of topics previously covered in his class. When I started using Direct Instruction programs I noticed that everything that students learnt was revisited. Rosenshine talks about the importance of daily, weekly and monthly reviews. Others frame it as retrieval practice. Whatever you call it, it is essential that we give our students the opportunity to revisit and build on their prior learning. Inspired by the practice of Bentleigh West PS, as demonstrated in this video by David Morkunas, I spend about 20 minutes in a revise phase reviewing things I have previously taught. This part tends to be paced pretty quickly, with students' understanding being regularly checked. One revise phase might cover the following:

Given the number of topics we touch on, it has to be paced quickly, and mathematical fluency is developed throughout. Students are constantly responding to questions in different ways and I am able to provide immediate feedback whenever an error occurs. I am also able to be responsive and anything that gets a high number of errors will be revisited and retaught. Any students who struggle are easily identified and provide additional support. Having said that, the success rate as we revise tends to be pretty high. 2. Learn The middle part of my Maths lesson (again about 20 minutes) is where the students learn because I am explicitly teaching. At the start of the year many of my foundation students didn't know how to count to 20. All of the concepts that now feature in our revise phase have been explicitly taught. During the learn phase new material is explicitly taught in small steps. Students are actively engaged as they build their knowledge about the concepts, procedures and strategies that are critical for being numerate. 3. Apply Once students have been taught a new concept, they need to be supported as they practice it. The apply phase provides dedicated time for students to apply their new knowledge in different situations. It is here, in the final third of our lesson, that students are supported as they solve problems and share their reasoning. It is important to note that this phase occurs after the explicit instruction. My students have been set up to succeed because they have been taught the skills they need to be successful. And because my students are successful at Maths, they love Maths! Keen to learn more? I am presenting about my experience teaching Maths at Sharing Best Practice Ballarat on October 1. Tickets have sold out but if you're attending then I'd love it if you chose to come to my session. Think Forward Educators have set up a Maths Network and the inaugural meeting on September 14 features non other than David Morkunas! Details can be found here. I recently came across an article that claimed ‘Phonics is not a panacea for all struggling readers’. This opinion piece, originally published in The Atlantic Journal-Constitution and then reposted on the Reading Recovery website, is a strange concoction of arguments. The authors seem to be arguing against phonics instruction while simultaneously claiming that phonics plays an important role in learning to read. The evidence that they draw on leaves readers completing bizarre mental gymnastics to try and discern the logic. The authors open with discussion about recent funds in Georgia and New York that are being allocated so that teachers can better support students with dyslexia. There is an acknowledgement that dyslexia potentially affects 20% of students. This is a decent opening before it launches us to an uneven parallel. Apparently, the real issue we should be focusing on to address reading is not what happens in our classrooms. Rather we should instead be concerned with the nutrition of our students. There seems to be an argument that we cannot teach children to read because they are hungry. Or maybe it is suggesting that we can only be concerned about one thing at a time. Either way this is an attempt to place blame for poor reading rates at the feet of families. The cry that families of dyslexic students hear all too often to “just read more” has been altered to “just feed more”. I have taught in a school where we have provided school meals. Too often students turned up to breakfast having not eaten since the lunch we had provided the day before. I am acutely aware of how hunger impacts on learning. To suggest that teachers are trying to meet the nutritional needs of students by teaching them how to read is absurd and demeaning. Teachers pride themselves on meeting the needs of our students. Teachers also recognise what is within our control. Whether a child receives the full nourishment that they need at home is simply not within the direct influence of schools. Claiming that hunger prevents teachers from delivering meaningful instruction underestimates the abilities of our educators. Teachers are amazing at meeting and understanding the needs of our students, within the scope of our training. While nobody wants a child to be hungry, we can still teach them when they are. Continuing to shift blame, the idea that proficient readers tend to read more than weaker readers is explored. This tendency causes the gap between them to continue to expand- sometimes referred to as the Matthew Effect. The cause of this gap is apparently to do with ‘reading habits’. This seems peculiar because I would have assumed that a fair chunk of this difference actually is to do with whether the child has the skills required to read. Someone who doesn’t know how to read is not likely to want to read! We need to ensure that we incorporate systematic phonics into our teaching of reading so that all students know how to read. Phonics is again questioned as the Orton-Gillingham program is considered. The fact that this program is not included in What Works Clearinghouse seems to be enough evidence for it to be ineffective. I will remind you that this article was republished on Reading Recoveries website and if you have missed the irony then please read this policy paper or this article. Having besmirched phonics, the ability of professionals to accurately diagnose dyslexia is called into question. Apparently, our children are being misdiagnosed and this has led to too much phonics. This completely ignores the fact that the instruction that best meets the needs of dyslexic students is the same instruction that best meets the needs of ALL our students. After criticising phonics, the importance of phonics is finally asserted. It turns out that the criticism has only been about ONLY teaching phonics. Which would be fine if such a school existed. Such a place does not exist. This article seems positioned to perpetuate this myths and further deepen a dichotomy that is not helpful. Phonics is not a panacea, but it is essential. It would not be enough to just eat iron, but it is an absolutely necessary part of our diet. Many people get enough iron in their regular diet. Some people need to take iron supplements. Some people learn to read without phonics instruction, but far too many do not. Enhancing reading instruction with phonics is vital for our children, with no side-effects. The Science of Reading does not support solely teaching phonics. Rather than pretending that phonics is an issue, we need to focus on how phonics instruction can support more of our children to become proficient readers. Our children, and their families, deserve to be taught how to read. |

I'm JamesI am a father of two (8 & 5), married to an incredible Early Childhood Educator. Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed